OPEN featuring Gherdai Hassell

by Kristin White of STILL VEXED

I was told to take my time, and schedule a day when I could sit in silence, alone. Settle my bones, give my marrow time to soak it all in. To be ready for the heaviness of my emotions. But, before this could happen, once again the island was locked down, and the doors were shut.

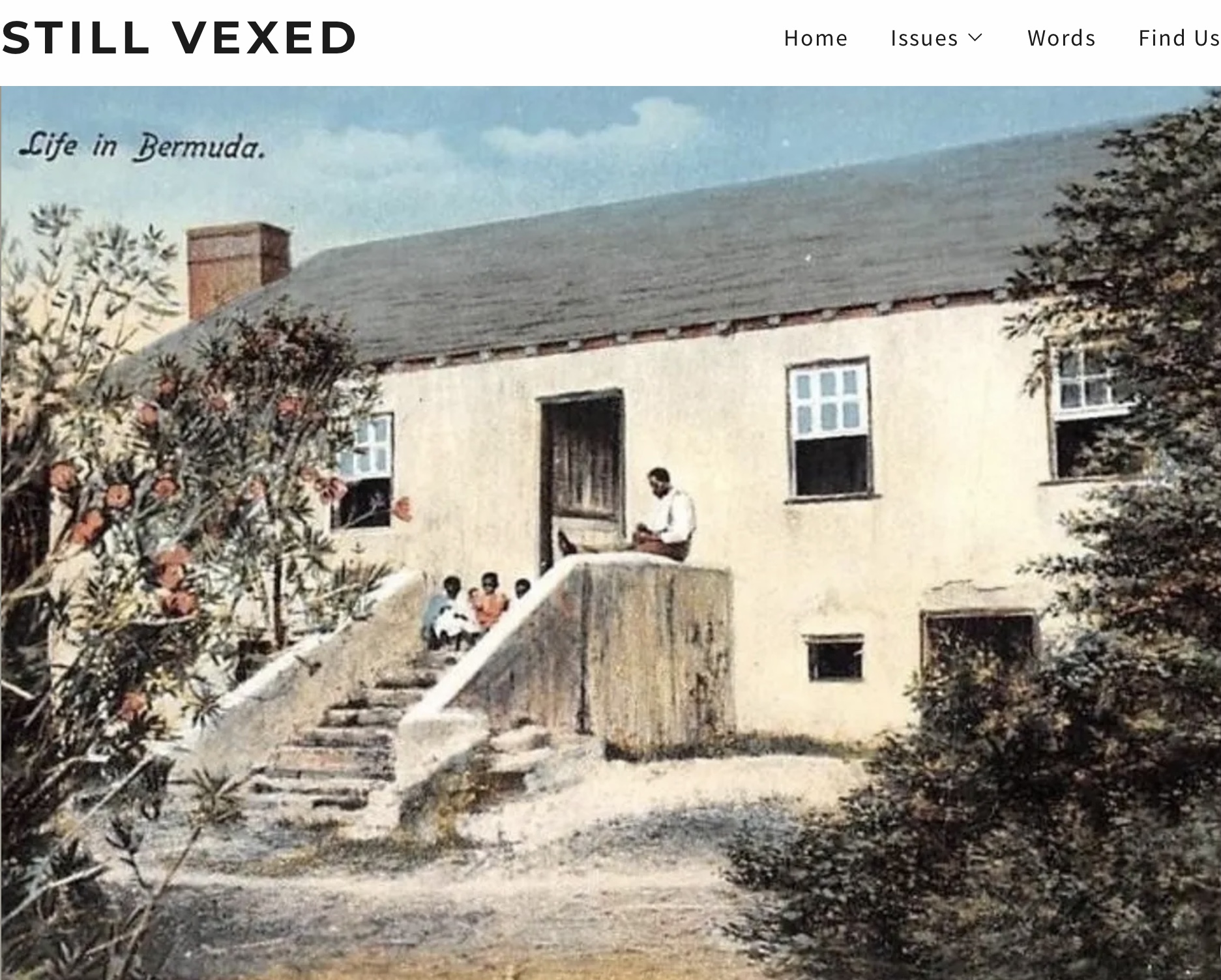

So, when I sat and had a conversation with Gherdai Hassell, the artist whose work had elicited this advice, I hadn’t yet seen her Bermuda National Gallery exhibit, ‘I Am Because You Are’, which opened in mid-March. The exhibit takes its title from a Zulu phrase that talks of our shared humanity and is a work of reimagining, of exploring her identity as a Black Bermudian descendant of enslaved people.

The gallery’s website has an ‘immersive virtual experience’, where I could view the exhibit, but it felt impersonal, lacking weight. So I decided to wait. Gherdai agreed. She told me to see it in person as she’d intended while creating this work, a journey that began a few years ago when she found her family tree amongst her aunt’s papers.

“I wanted people to walk into the space, and have them be able to imagine what their history might have been.”

The discovery of this tree changed Gherdai’s life, and started to further shape her understanding of her identity.Unlike many of us who are descendants of enslaved African people, and have no records beyond a few generations, her ancestry can be traced all the way back to ‘Papa Short’, a man stolen from Africa in 1824.

“Looking back and reflecting, I can see how I’m connected to the wider diaspora. And everything about who I am as a person and my identity is steeped in being Bermudian.”

This realisation came recently for Gherdai. During her childhood, she didn’t engage much in traditional Bermudian heritage activities, and her interest in art sometimes had her feeling isolated from her peers, disconnected to the island. Like so many other Bermudians, it wasn’t until she left and experienced living overseas, that she formed a full appreciation for Bermuda’s unique culture.

Gherdai was studying law in the UK when she decided to give up her scholarship, and pursue her passion for art. After researching places where she could find artistic inspiration, a low cost of living and access to inexpensive high-quality art supplies, she decided Asia was her best option, and obtained a certification to teach English. Although Korea was her first choice, an offer came from a Chinese company, and after minimal research, she found herself there.

“The first few weeks were extremely difficult.”

Lost luggage.

A massive language barrier.

And being the only Black person that many Chinese people had seen meant she was constantly on display, being photographed and touched when she walked around.

Gherdai wasn’t sure if she could stay… but told herself to stick it out for a month. Then three months. Six. And then she figured she could make it the full year of her contract. After that ended, she received an offer from another school, this time, a school that incorporates art.

It was here that she was introduced to her now-mentor and professor who recommended her to attend the China Academy of Fine Art, where she was accepted into a graduate programme. The summer before Gherdai began, she visited Bermuda, and found her family tree. This, plus her immersion in Chinese culture had her questioning her own.

“China brought me back to myself.”

The nationalism and strong sense of identity she saw, and her sense of feeling so othered there, had her digging for answers. After all, every time she left her house, she was ‘under a magnifying glass’. “Everyone was looking at me… it made me look at myself. I began to think about what it means to be a Black woman. What it means to be Bermudian”

With lots of solitude, and time to reflect, Gherdai began to use her art even more to deal with what she was going through.

“I really think I needed to be placed out of context, out of my original home base, to figure out that home is within me first. That is what carried me through the challenging times in China. I got introduced to a different side of myself. Resilience. Determination. I developed a laser focus on what I wanted to do with my life and artwork, which I feel is tied into my purpose.”

During this time, Gherdai read the book Homegoing by Yaa Gysai, an award-winning novel that follows the story of two sisters, one sold into slavery and one that remains in Africa, tracing their descendants to modern day. The story moved her so greatly that she aspired to create a work that would create a similar reaction for others, and one that was steeped in bloodlines.

“I have visited my aunt, looked through the papers, so many times. Maybe I passed that family tree before and never noticed. The magic in the work is being able to pay attention. To have the awareness that art is happening all around us. To recognise things that have always been there, and be able to name it for what it is. If we are focused, in the right frame of mind, we can pick up the little whisper.”

Following the little whisper led Gherdai to the Bermuda Archives, where she laid eyes on the Slave Register, and portraits by N. E. Lusher for the first time. From here, she describes a Spirit, who saw her as an open vessel, and led her to begin thinking about this work of reimagining.

“I didn’t just want to make a pretty picture. When I think of Bermuda art, it’s pastels and pretty pinks. But there are so many social issues that we experience in Bermuda that need to be discussed and art is an amazing way to be able to comment on the things we have to navigate through as a community.”

The Covid pandemic meant Gherdai had to quickly leave China early last year, of course not knowing that 18 months later, she still would not have returned. Leaving what had become a home for her, to join her mother and sisters in the UK felt a bit like displacement, and again had her questioning where she belonged. But it was here, alongside family and with a backdrop of the Black Lives Matter, that she was able to dig deeper into the work she’d been conceptualising.

“I wouldn’t have been able to make this monumental work in China. I needed to be home with my family.”

Earlier this year, she left the UK to mount and open her exhibit, and was both surprised and affirmed by the visceral reaction of Bermudians who came to view the work. Her goal to create work with meaning, to open a dialogue about Bermuda’s painful past, and to provide a space for Black people to see themselves as beautifully resilient was accomplished.

As she looks forward, beyond the success of her first solo show, Gherdai plans to use her art ‘as a mirror’ to reflect images of Black joy and peace, while continuing to ground her work in history, culture and her home, Bermuda.

“I am living in, embodying my purpose, so it, too, is a home.”

—

Gherdai’s name is pronounced ‘jer-day’, with greater emphasis on the second syllable. Her exhibit “I Am As You Are” runs until September 21 at the Bermuda National Gallery. As I write this, the gallery is open to the public, and I am scheduled to visit tomorrow.

This writing is published in the Spring 21 issue of Still vexed. Read the letter from the Editor Kristin White here